While urban sociality seems at times to be ruled by the constancy of everyday practices, at others that reliability is revealed as artifice by the capricious instability of our economic and political structures. The routine intimacies of our lives are punctured by the dysfunction of the material foundations that make them possible. In urban spaces in the global South, such as Sanaa, those ruptures may become so familiar as to be ritualized, serving as the basis for new forms of cultural expression and social action.

The work of Salwa Aleryani, a Yemeni painter and sculptor with a talent for intimate and insightful conceptualizations, negotiates this juncture between the commonplace and the extraordinary. In this interview, conducted over the course of a number of conversations and email exchanges in July and August 2013, Salwa addresses the relationship of her creative process to both singular personal experiences and broader social transformations.

Salwa Aleryani is an artist based in Sanaa, Yemen. Following a BA in Graphic Design from the University of Petra, she was awarded a Fulbright scholarship and later received her MFA in Painting from Savannah College of Art and Design. With a combination of interests in gendered space, dwelling, and public infrastructures, set against intimate objects and rituals, her work has recently taken a number of directions that are both parallel and divergent. Recently, she was in residence at Dar Al-Ma’mun Foundation in Marrakech and Art OMI in New York, and was awarded the Young Arab Artists Production Grant from the non-profit arts organization Al Mawred Al Thaqafy. Her website, with information of past projects and future showings, is found at: http://www.salwaaleryani.com/

John Warner (JW): Your work appears at times to challenge the boundaries of normative artistic practice in your homeland. How do you negotiate issues of authenticity and tradition in your art? How do you mediate between the conventions of a particular (local or national) artistic vocabulary and an appeal to more universal experiences?

Salwa Aleryani (SAE): While some aspects of my work seem to challenge what is considered the norm in local practices, there are other aspects that operate very much within it. Whether that is an accomplishment or a limitation, I cannot say. I have often utilized common motifs and materials that have their local origins, such as plaster, which is used in traditional architecture throughout much of Yemen, but also just familiar things like brushes, mattresses, and utility bills that are identified locally in their particular form, but can be understood generally in function. In reality, in the process of creation, I am not explicitly concerned with the question of whether it speaks universally or not. It is a much more intuitive process than that. Broadly speaking, I have an affinity towards work that disappears into the background, but without being completely lost. I operate on this inclination, where the work slowly unfolds, allowing for multiple readings without the risk of being estranged. I rely on the fact that the art itself mimics its subject. At best, from where I stand, it occupies a modest space and is in closer proximity to an audience that stands at differing angles to it.

[Once Upon a Pocket (2011) – Etched mirror on plastic brushes.]

JW: Your art seems to revolve around that which is most mundane. You coax the commonplace or ordinary—doormats, manhole covers, hairbrushes—into speaking to some of the most fundamental aspects of our lived experience. What is it about mundanity that makes it such a powerful artistic vehicle?

SAE: Is it not easier to obsess over trivial and mundane things, compiled and collected stuff, and to take on their meanings? It is a practice that reminds me of John, a protagonist in Virginia Woolf’s Solid Objects who gives up politics after developing an obsession with mundane things. For him, “any object mixes itself so profoundly with the stuff of thought that it loses its actual form and recomposes itself a little differently in an ideal shape which haunts the brain…” I too am interested in the ability of mundane things to circulate, disclose, and be carried away as facts. This is suggested in Once Upon a Pocket (2011), a piece made from over twenty rectangular mirrored plastic brushes that are often sold by street vendors in Sanaa and, once bought, are kept pocket-close so as to not let a hair stray out of place. A mirror, for the most part, casts a fleeting reflection of a visible surface, whereas here it not only allows a glimpse into a concealed pocket, but also offers an etched image of it.

[One Moment After (2011) – Plaster, wood, electric boxes, ink, and drywall.]

JW: The “unseen” has been a theme in much of your work, manifested, for example, in the wood lattice that undergirds a plaster wall in One Moment After (2011) and the masbaha beads sequestered in someone’s pocket in Once Upon A Pocket (2011). Here, your art is literally a revelatory process. What do you find so important in this act of uncovering?

SAE: Although the process of uncovering runs through my work, it tends to fluctuate in terms of what it embodies. At times, it follows a curiosity because discovery holds promise, and at others, it is an impulse to reconcile what is visible with what is hidden. Either way, I often return to it not because of its theatricality, but because of its capacity to facilitate a slower leakage of bits and pieces. To me, alongside the work you mention, Sewer Cover (2011) has this potential. It is made from a loosely cast soil cover embedded in carpet, and when you witness it crumble, it reveals a sequence of thoughts—one being the fact that the very material it is made out of is that from which it sets out to protect us. It is light in weight, but its immobility carries a burden similar to that of a heavy iron cast. Unashamed, it suggests that it is no longer reliable, and that at the slightest wind, it could blow away, leaving behind an unearthed cavity. Turned inside out, there is a sense of unease when it spills out of its boundary and recedes into carpet. Though, in every respect, dirt is not alien to carpet, still it intrudes on it. It does so in a way that seems familiar, as it would on a person that neglects to attend to cleaning his house over an extended period of time.

[Sewer Cover (2011) – Soil and Carpet.]

JW: Your piece Current View (2011) scrapes away formal surfaces to look at their structural underpinnings. The corroded framework and exposed empty spaces suggest that you view these structures as somehow unstable, incomplete, and potentially illusory. Given the rootedness of your art in the everyday experiences of social life, what does this piece attempt to communicate to us?

SAE: In a way, this work considers the possibility both of a structure that existed and crumbled over time and of one that is “new” and under construction, but abandoned midway through. While working, I would bury the elements in blocks of plaster, paying little attention to marking where they were located exactly, and then would desperately try to unearth them. In retrospect, through this futile exercise I struggle with the idea of disintegration verses abandonment, and how that could be read in the qualities of solidity and fragmentation of structures as we witness them today. These structures are edifices, again both new and old. They may have once stood high, but then fell into decay, or always existed as foundations, but were never built upon. Mostly, they are dwellings—they are intimate, private, and protected. Exposure is unwanted and a halt in their construction is an incompleteness of living.

[Current View (2011) – Plaster, wood, ink and electric boxes.]

Essentially, if a wall shed a layer or two, a fissure chipped away, or a section came off, its inner elements become exposed and the foundation of its structure seem uncertain. I am interested in probing this uncertainty not to seek an answer, but to establish a quest. Also, like other public services screened from view, wires and sockets embedded within the walls and ceilings of our living spaces constitute a complex layer that is integral to their functioning. So, when an outlet is bare or abandoned, both domestic and public infrastructures come into question. In elucidating this incompleteness, I draw on my own experience of witnessing the gradual erosion of the built environment, the social structures to which we belong, and the infrastructural networks and technological systems on which we depend.

JW: Your Sleeper (2012) (see above), Where to Crash (2012), and other related works may be read as testaments to the subversive potential of everyday social practices. As opposed to statements such as Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981), which averred the absolute structuring power of barriers, this body of work illuminates the transformative effects of children’s play and smoke breaks on one of the most widely visible mechanisms of state control in Yemen—the checkpoint barricade. Can you tell us about the context out of which this work emerges and the process through which it was created?

SAE: Taking my work with doormats as a juncture, when I moved towards an outdoor context I became interested in the idea of feeling “at home” in public. The not-so-sudden increase in the number of roadblocks in Sanaa over the past few years, erected by state actors as well as non-state entities, coincided with a sudden observation on my part. Though they were deployed with the intention of deterring and shaping the movement of people, vehicles, goods, and weapons, those efforts at exerting control were frequently thwarted. Often, people would lounge, sit, or lean against them completely at ease, sipping tea and going about their daily activities. I was rather intrigued by this phenomenon and its connotations and wanted to both document and visualize it.

[Where to Crash (2012) – Video Still.]

My point of departure was the mattress paired with concrete. Alternating between soft foam, upholstery, and concrete seemed to trigger an odd conversation on the difference between resting and stopping, comfort and suffocation. While I still find that these interactions testify to the subversive potential of everyday practices, in the process I could not help but think that the hybridity also pointed to the possible dual outcome of this subversion. In one way, the impact of roadblocks may have been softened, but in another, our mattresses may have hardened. In other words, I am raising the possibility of this being a state of normalization rather than reclamation, where the hostility and power of these constraints becomes internalized, perhaps even embodied.

JW: The metaphorical dualism of darkness and light has long been used in the history of art, but your current project Where were you when the lights went out? addresses them more as lived material reality. How does this work bring the (un)predictability of electricity and the cultural practices that arise from its irregular presence to the center of a conversation about modernity?

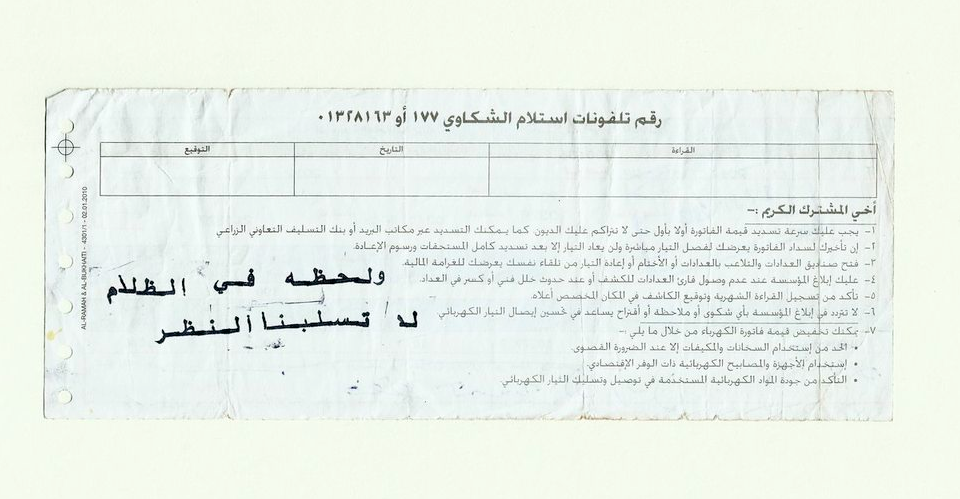

SAE: It comes from a place or rather a question of dependency, as well as of abundance. Yemen produces more than enough oil and natural gas to generate electricity for the entire country, but blackouts are now a daily occurrence in Yemen, with power outages lasting for hours, if not days, at a time. The nature of the state, the flow of services, and what it means to rely on a structure that is unstable or on the verge of collapse. Weaving poetry into electricity bills, as I do in A moment in the dark does not blind us (2012), means mixing two languages that measure light and dark through different systems, but that nevertheless have a similar economy, which is that of resourcefulness. To add to that, against a backdrop of frequent blackouts due to acts of sabotage, a failing infrastructure, or otherwise, what happens when these two are placed parallel to each other? How is expressive language read against an exchange that is mostly reserved and perhaps even problematic? Is it an error that replaced numbers with letters or is it calculated?

[A moment in the dark does not blind us (2012) – Passage from Pablo Neruda’s “Critical Sonata” – Ink on Electricity Bill.]

When these questions arise the conversation comes in. Another part of the project takes sound into consideration, allowing an orchestra of generators to compose itself, the work carries an essence of romanticism that is in no way romantic because it is very much grounded in reality – a disruptive reality, which dictates that masses of generators run at the same time, when available, to compensate for this shortage. The mobilization of this noise pokes at this, and other nuances already found in the practices that people took on as a result of this shortage. If anything, the work does not seek to condemn. Rather, it looks towards the hopefulness in these gestures and, in a way, depends upon an abundant faith amid little expectation.

[Where were you when the lights went out? – Generator on Jamal St. I – Color Photograph.]